How to Avoid Being Upside-Down on a Car Loan

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

The estimated reading time for this post is 206 seconds

How to Avoid Being Upside-Down on a Car Loan

“Upside-down” used to describe mortgages after the housing crash. Now it’s showing up in driveways.

Being upside-down on a car loan (having negative equity) means you owe more than the car is worth. If the car is worth $18,000 and your loan balance is $24,000, you’re $6,000 underwater. That’s not just a math problem. It’s a trap when you need to sell, trade in, or if the car gets totaled.

This isn’t rare anymore. In 2025, more than a quarter of new-vehicle trade-ins were underwater, and the average negative equity was roughly $6,700–$6,900. In some recent quarters, around 24–39% of drivers who financed a vehicle were underwater. (Sources: Edmunds, CarEdge/Black Book, major news outlets)

So the question is no longer “Do people really get upside-down on cars?” The question is “How do I keep my household out of that mess?”

What Does “Upside-Down on a Car Loan” Actually Mean?

Being upside-down—or having negative equity—means:

- Loan balance > Car’s current market value

Example:

- Your loan balance: $25,000

- Your car’s value: $20,000

- Negative equity: $5,000

This becomes a problem when:

- You want to trade in and the dealer offers $20,000. Your $5,000 shortfall gets quietly rolled into the new loan.

- Your car is totaled or stolen. Insurance pays you the car’s value, not your loan balance, and you’re on the hook for the gap unless you have gap coverage.

- You’re struggling with payments, but you can’t sell the car for enough to clear the loan.

Are you above water, barely afloat, or upside-down?

Enter your current payoff amount and your car’s estimated value.

Equity:

Loan-to-value (LTV):

Tip: Aim to keep your LTV under 100% as soon as possible. The lower it is, the more flexibility you have.

Why So Many Drivers Are Upside-Down Right Now

Negative equity didn’t just appear out of nowhere. It’s the result of a bunch of trends hitting at the same time:

- Record car prices. The average new car price has pushed past $50,000 in 2025 in the U.S. (Source: Kelley Blue Book data reported in major outlets)

- Longer and longer loans. Average loan terms have climbed to around 69 months, with 84-month loans making up a growing share of new loans. (Source: industry financing reports)

- Little or no down payment. With prices so high, many buyers put very little down—sometimes nothing.

- Rolling negative equity forward. Buyers trade in cars they already owe too much on, then roll that shortfall into the next loan.

Regulators have noticed. A 2024 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau report on negative equity found loan-to-value ratios over 119% on average when negative equity was financed into a new deal. (Source: CFPB report on negative equity in auto lending)

That’s how you get a household driving a car that’s worth $30,000 while owing $36,000 or more—and wondering why they can’t ever seem to escape their payment.

How You End Up Upside-Down on a Car Loan

1. Tiny or zero down payment

If you finance almost the entire purchase price, plus taxes and fees, your loan starts out very close to—or above—the car’s real value. Add in rapid first-year depreciation and you’re underwater almost immediately.

2. Extra-long loan terms

A long loan (72–84 months) makes the monthly payment look tolerable, but the balance drops slowly while the car’s value drops quickly at first. For years, the loan can be ahead of the car’s value.

3. Overpaying for the car

During the COVID supply crunch, lots of buyers paid thousands over MSRP. That inflated starting point still haunts borrowers who financed those cars at high prices and high rates.

4. Rolling negative equity into the next car

If you’re already upside-down and you trade in anyway, the leftover balance doesn’t disappear. It gets rolled into the new loan, often without you fully realizing how big that number is. Do this a few times and you’re stacking debt faster than you’re paying it off.

5. High-rate loans

Borrowers with weaker credit are stuck with higher interest rates that keep balances higher for longer. Delinquencies on subprime auto loans have hit record highs, which tells you how much strain these loans are putting on lower-income households. (Source: Fitch data, news reports)

How to Avoid Being Upside-Down in the First Place

You can’t control everything (like market prices), but you can control how aggressive you are with your loan terms and car choice. Here’s how to tilt the odds in your favor.

Quick-and-dirty check on your next car deal.

Estimate the deal you’re considering. This tool uses simple assumptions to flag high-risk setups.

Approximate starting loan-to-value (LTV):

Down payment percentage:

This is a rough guide, not a crystal ball. But if you’re red here, you’re likely to be upside-down for years.

Strategy #1: Put real money down

A 20% down payment is still a strong rule of thumb if you can swing it. At minimum, put down enough to cover the first-year depreciation so your loan balance doesn’t instantly start behind the car’s value.

Strategy #2: Keep loan terms tight

Try to keep loans at 60 months or less when possible. If the only way you can “afford” the car is with a 72- or 84-month loan, that’s not affordability—it’s a warning sign.

Strategy #3: Buy less car than the bank says you can

Banks approve you based on their risk of not getting paid back, not based on whether the loan leaves any room for savings and investing. For middle-class households, that gap is where negative equity and financial stress live.

Strategy #4: Avoid rolling negative equity into the next deal

If you’re already upside-down, the most important thing you can do is stop the cycle. Keep the car, pay it down, and drive it long enough for the loan balance to fall below the value.

Strategy #5: Choose boring, reliable, and reasonably priced

The more modest the vehicle compared to your income, the easier it is to pay off quickly and stay above water. Reliable sedans, crossovers, and smaller SUVs often hold value better relative to what middle-class budgets can handle than luxury or niche models.

Habits that sink you vs. habits that keep you safe.

| Pushes You Underwater | Protects You |

|---|---|

| Zero down or tiny down payment | Saving for a meaningful down payment (ideally 10–20%) |

| 72–84 month loan terms on expensive cars | 48–60 month loans on reasonably priced cars |

| Trading in every few years and rolling negative equity | Keeping cars well past the last payment and banking the savings |

| Buying at or above your approval amount | Choosing a car comfortably below what the bank says you can borrow |

| Ignoring the total cost of ownership | Budgeting for payment, fuel, insurance, maintenance, and taxes together |

Already Upside-Down? Here’s How to Climb Out

If you ran the calculator and you’re already underwater, you’re not alone—and you’re not doomed. But you do need a plan.

1. Keep the car and keep paying

Often the best option is also the most boring one: keep making your payments until the balance drops below the car’s value. As you pay down principal and depreciation slows, your equity position slowly improves. (This approach is echoed by many consumer finance guides and lenders.)

2. Add extra principal when you can

Extra payments directly to principal accelerate your equity. Even $50–$100 a month can shorten the time you’re underwater. Make sure your lender applies extra to principal, not just prepaying future interest.

3. Don’t roll the shortfall into another car

Trading out of a car you’re upside-down on is tempting, especially if the new car feels more “affordable” each month. But when you roll negative equity forward, you’re digging the hole deeper. The next car starts life underwater too.

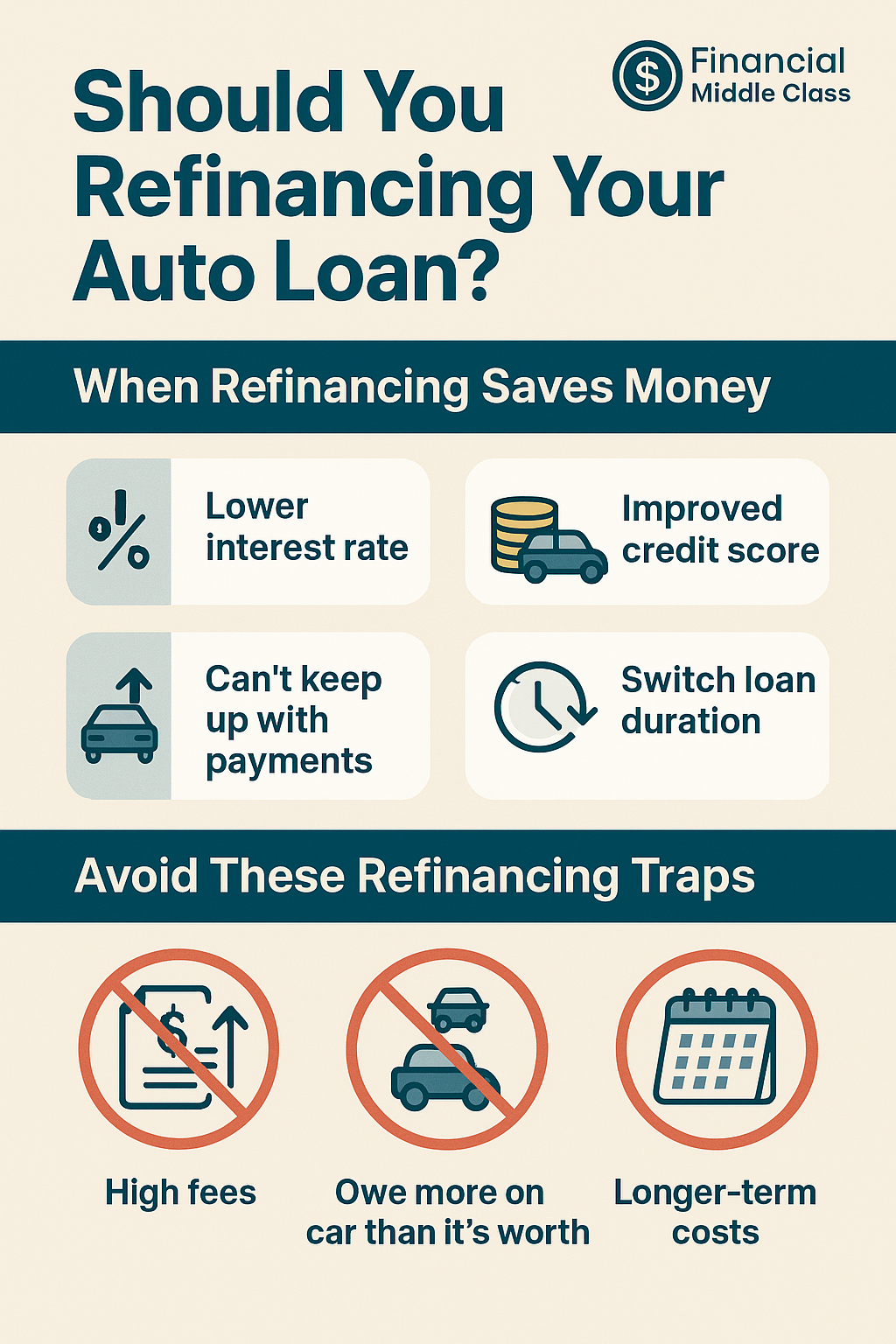

4. Consider refinancing—carefully

If your rate is high and your credit has improved, refinancing into a lower rate and/or shorter term can help you outpace depreciation and reach positive equity faster. (Source: bank and credit union guidance)

5. Protect yourself with gap coverage if you must drive underwater

If you’re temporarily stuck with a high loan-to-value ratio, gap insurance can protect you from writing a giant check if the car is totaled. It doesn’t fix the underlying debt, but it can prevent disaster while you work your way back to even.

FAQ: Upside-Down Car Loans

How common are upside-down car loans?

Very. Recent industry data shows that well over one in four trade-ins are underwater, and some reports put the share of financed drivers with negative equity as high as the high 30% range in certain quarters.

Is being upside-down always bad?

If you plan to keep the car, drive it for years, and can comfortably make the payments, a little negative equity isn’t an emergency. It becomes a problem when you need to sell, trade, or if the car is totaled.

Should I sell my car if I’m upside-down?

Selling only makes sense if you can cover the shortfall in cash and move to a much cheaper, more sustainable vehicle. Otherwise, you may just be shuffling debt around.

Can I trade in a car with negative equity?

Yes—but the shortfall doesn’t go away. It gets rolled into the new loan, which is exactly how people get trapped in a cycle of permanent car debt.

What’s the safest way to buy a car and avoid negative equity?

Save a real down payment, choose a car below your “approval amount,” stick to a reasonable loan term, and plan to keep the car for years after the last payment. That combination gives you margin and flexibility.

The Bottom Line: Your Car Should Move You, Not Trap You

Negative equity is not just a car problem; it’s a mobility problem. When you’re upside-down, you lose options. You can’t downsize easily. You can’t sell and reset. You’re stuck feeding a loan for a car that’s already given the best years of its value to the bank.

You don’t have to play that game.

- Put real money down when you can.

- Keep the term tight.

- Choose cars your income can actually support.

- Stay in them long enough to enjoy life with no payment.

For the middle class, that’s not just “good car advice.” It’s how you carve out the extra cash flow you need to kill high-interest debt, build an emergency fund, and invest for your future instead of the bank’s.

Check Your Equity Before You Sign Anything

Use the Car Equity Snapshot and Upside-Down Risk Preview tools on this page before you agree to any new car deal. If the math says you’ll be underwater for years, believe it—and change the deal instead of trying to outwork the numbers.

For more middle-class money playbooks like this, join the Financial Middle Class newsletter. We walk through the math, the traps, and the moves that actually build wealth.

RELATED ARTICLES

Trump’s 401(k) Down Payment Plan: A House Today, a Retirement Tomorrow?

Could Trump let you use 401(k) money for a down payment? Learn how it works, risks to retirement, and price impacts—read first.

The One-Income Family Is Becoming a Luxury. Here’s the Salary It Takes Now.

How much must one parent earn so the other can stay home? See the real math, examples, and tradeoffs—run your number now.

Leave Comment

Cancel reply

Gig Economy

American Middle Class / Jan 19, 2026

Trump’s 401(k) Down Payment Plan: A House Today, a Retirement Tomorrow?

Could Trump let you use 401(k) money for a down payment? Learn how it works, risks to retirement, and price impacts—read first.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 18, 2026

The One-Income Family Is Becoming a Luxury. Here’s the Salary It Takes Now.

How much must one parent earn so the other can stay home? See the real math, examples, and tradeoffs—run your number now.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 18, 2026

Credit Cards vs. BNPL: Which One Actually Works for the American Middle Class?

Credit cards vs BNPL: costs, risks, and the best choice for middle-class cash flow. Use this 60-second framework—read now.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 18, 2026

The Affordability Pivot: Can Trump’s New Promises Actually Lower the Middle-Class Bill?

Will Trump’s affordability proposals lower your bills—or backfire? Housing, rates, tariffs, gas, credit cards—explained. Read now.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

Business / Jan 13, 2026

Starting a Nonprofit Is Easy. Starting the Right Nonprofit Is the Hard Part.

The estimated reading time for this post is 880 seconds Last updatedJanuary 13, 2026 — Updated for IRS e-filing pathways (Pay.gov), the 501(c)(4) notice requirement, and...

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 12, 2026

America’s 25 Fastest-Growing Jobs—and the part nobody tells you

BLS lists 25 fast-growing jobs for 2024–2034. Learn what it means, avoid traps, and pick a lane that fits your life—read now.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 12, 2026

Is It All Glitter? The Middle Class and the Gold Craze

Should the middle class buy gold? Learn who’s buying, hidden costs, and smarter hedges—plus a simple test. Read now.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 11, 2026

Hey, California: Tax Loans Backed by Capital Assets, Not

California’s billionaire tax misses the point—tax asset-backed borrowing, not paper wealth. Read the argument and decide.

By MacKenzy Pierre

American Middle Class / Jan 11, 2026

“People live in homes, not corporations.” Now what?

Do big investors drive housing costs? A neutral, data-backed look at the evidence, tradeoffs, and what a ban could change. Read now.

By FMC Editorial Team

American Middle Class / Jan 09, 2026

Debt Statute of Limitations: The Clock You Didn’t Know Was Ticking

Learn how debt statutes work, avoid resetting the clock, and protect yourself from lawsuits. Read before you pay.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

Latest Reviews

American Middle Class / Jan 19, 2026

Trump’s 401(k) Down Payment Plan: A House Today, a Retirement Tomorrow?

Could Trump let you use 401(k) money for a down payment? Learn how it works,...

American Middle Class / Jan 18, 2026

The One-Income Family Is Becoming a Luxury. Here’s the Salary It Takes Now.

How much must one parent earn so the other can stay home? See the real...

American Middle Class / Jan 18, 2026

Credit Cards vs. BNPL: Which One Actually Works for the American Middle Class?

Credit cards vs BNPL: costs, risks, and the best choice for middle-class cash flow. Use...