The Asymmetrical Relationship Between Middle-Class Americans and the Largest U.S. Banks

By FMC Editorial Team

The estimated reading time for this post is 347 seconds

Abstract

Middle-class Americans maintain a structurally unequal relationship with the country’s largest banks. This asymmetry stems from persistent financial literacy gaps, the complexity of modern banking products, behavioral design that nudges consumers into costlier outcomes, and the scale advantages enjoyed by megabanks. Although regulators intervene episodically—most visibly in cases like Wells Fargo’s fake accounts scandal or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) campaign against overdraft and “junk fees”—the imbalance endures. This article examines the origins, manifestations, and consequences of this asymmetry, evaluates regulatory responses, and explores both policy-level and household-level interventions to reduce the disparity.

Introduction

The middle class remains the backbone of the American economy, representing both the largest consumer base for banking services and the most profitable segment for fee-based products. Yet the relationship between middle-class households and the country’s largest banks has long been marked by imbalance. Banks operate with informational, structural, and institutional advantages, while the average consumer engages with limited literacy, constrained choice, and high switching costs.

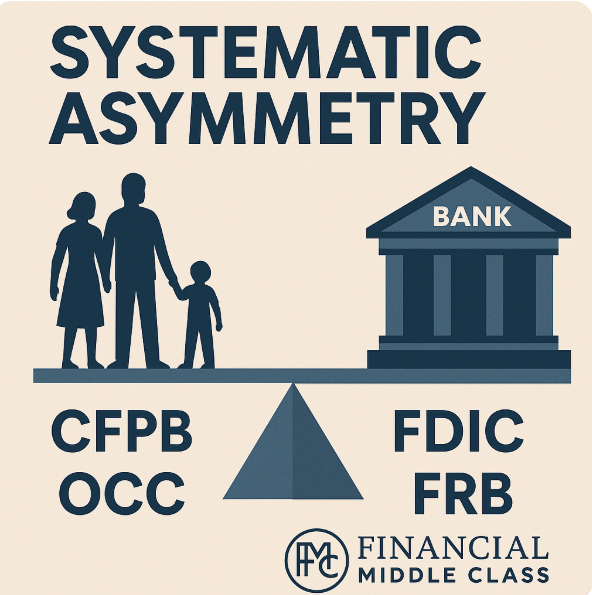

The result is what behavioral economists would call a systematic asymmetry: one party consistently has more power, knowledge, and control over outcomes than the other. This imbalance matters not just for household well-being, but for systemic trust in financial institutions and the legitimacy of U.S. consumer finance regulation.

The Financial Literacy Gap: A Foundational Imbalance

Financial literacy in the U.S. remains stubbornly low. FINRA’s 2025 National Financial Capability Study reports that only 27% of Americans answered at least five out of seven basic financial knowledge questions correctly. That number has barely moved in a decade, despite expanded financial education initiatives.

By contrast, European and East Asian countries that embed financial literacy into national curricula achieve higher performance. For instance, the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results consistently show U.S. teenagers lagging behind peers in places like China, Estonia, and Australia on financial literacy metrics.

This knowledge deficit shapes everything from the ability to interpret fee disclosures, to understanding compound interest on credit cards, to recognizing the risks of overdraft products. In practice, it ensures that banks can design products whose risks are invisible to most customers until after harm occurs.

Complexity and Behavioral Design in Banking Products

Even financially savvy consumers face challenges navigating the modern banking environment.

- Fee structures are opaque. Overdraft charges may be triggered multiple times in a single day, rewards cards tout “points” without clear monetary equivalents, and teaser rates obscure the long-term costs of borrowing.

- Behavioral nudges are built into design. Default settings—such as automatically enrolling customers in overdraft “coverage” instead of decline-only—maximize fee collection. Interface design often highlights credit offers while minimizing savings options.

- Switching costs reinforce inertia. Changing banks involves moving direct deposits, automatic bill payments, and linked accounts, creating logistical hurdles that dissuade consumers from leaving even when they recognize predatory practices.

These dynamics illustrate what legal scholars call exploitative choice architecture—arrangements that systematically benefit the institution at the consumer’s expense.

Case Studies in Asymmetry

Wells Fargo: Manufactured Accounts

Between 2009 and 2016, Wells Fargo employees created millions of unauthorized accounts to meet aggressive sales targets. Customers were often unaware until fees or credit report impacts emerged. Regulatory responses included billions in fines and restitution, yet the scandal persisted for years before it was uncovered.

Bank of America: NSF Fees and Withheld Rewards

The CFPB and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) ordered Bank of America to refund $80.4 million in 2022 for unfairly charging multiple NSF fees on the same transaction. In a separate case, the bank was fined $150 million for withholding credit card rewards and creating unauthorized accounts.

Zelle and the Rise of Real-Time Fraud

The adoption of real-time payment networks like Zelle has created new vulnerabilities. In 2024, the CFPB sued JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo for allowing fraud to “fester” and for failing to reimburse victims under federal law. Banks have since begun tightening policies, such as blocking payments linked to social media sales. Still, consumers bear most of the risk in systems designed to move money faster than fraud detection can intervene.

Regulatory Oversight: Episodic and Uneven

The CFPB’s Role

Since its establishment in 2011, the CFPB has served as the leading federal consumer watchdog. Its initiatives against overdraft and “junk fees” have reduced household costs—overdraft and NSF revenue dropped by 51% between 2019 and 2023. Yet enforcement is often reactive: penalties arrive long after consumers have been harmed.

The Banking Agencies (OCC, FDIC, Federal Reserve)

These agencies supervise banks for “safety and soundness” as well as compliance. They have issued consent orders for failures in third-party risk management, particularly as banks expand into fintech partnerships (Bank-as-a-Service). However, their focus traditionally leans toward protecting the stability of the banking system rather than directly safeguarding consumers.

Political Flux and Regulatory Scope

Proposals to narrow supervisory authority—such as removing “reputation risk” from oversight—illustrate how politics influence consumer protection. A shift in regulatory philosophy could reduce pressure on banks to address practices that, while technically legal, may be harmful to middle-class households.

The Consequences for Middle-Class Americans

The cumulative effect of these dynamics is measurable in dollars and stress:

- Households paid billions annually in overdraft and junk fees until very recently.

- Credit report damage from unauthorized accounts and late-fee spirals can affect borrowing costs for years.

- Real-time payment fraud exposes families to losses with little recourse.

- Persistent distrust in banks undermines consumer confidence, driving some households into high-cost alternatives like payday lenders or check-cashing services.

Toward Reducing the Asymmetry

Policy Recommendations

- Plain-Language Cost Disclosure: Require standardized fee dashboards showing typical monthly costs under common usage scenarios.

- Safe Account Defaults: Mandate that banks offer a low-fee, overdraft-free account as the default product for new customers.

- Fraud Liability in Real-Time Payments: Extend consumer protections from credit cards (zero-liability rules) to instant payments.

- Strengthened Third-Party Oversight: Ensure that fintech partnerships remain accountable under the same standards as traditional banks.

Household-Level Interventions

- Quarterly Fee Audits: Families should review quarterly statements to calculate total fees paid and explore alternatives if the cost exceeds $100.

- Opt Out of Overdraft Coverage: Request decline-only settings to avoid cascading fees.

- Zelle and Cash Equivalence: Treat real-time transfers as irreversible cash; use only with trusted contacts.

- Automated Safeguards: Set up alerts for low balances, large withdrawals, and due dates.

Conclusion

The relationship between middle-class Americans and the nation’s largest banks is not merely transactional; it is structural. Asymmetry is baked into the system through financial illiteracy, product design, institutional scale, and uneven oversight. Regulators can—and sometimes do—intervene, but the pace of enforcement rarely matches the speed of harm.

If the U.S. is to build a fairer banking system, reforms must address both sides: policies that reduce exploitative practices and consumer empowerment strategies that arm households with knowledge and tools. Until then, the imbalance will persist, and the middle class will remain vulnerable in a system that depends on their deposits but profits disproportionately from their missteps.

RELATED ARTICLES

How Wealth Is Passed Across Generations in the United States: Mechanisms, Evidence, and the Policy Debate

How wealth passes between generations—trusts, taxes, and the debate. Get the facts, figures, and tradeoffs. Read now.

The S&P 7,000: How Wall Street Disconnects from Main Street

S&P 7,000 can rise while wages, benefits, and towns fall behind. See why the market isn’t the economy—read now.

Leave Comment

Cancel reply

Gig Economy

American Middle Class / Feb 18, 2026

How Wealth Is Passed Across Generations in the United States: Mechanisms, Evidence, and the Policy Debate

How wealth passes between generations—trusts, taxes, and the debate. Get the facts, figures, and tradeoffs. Read now.

By FMC Editorial Team

American Middle Class / Feb 16, 2026

The S&P 7,000: How Wall Street Disconnects from Main Street

S&P 7,000 can rise while wages, benefits, and towns fall behind. See why the market isn’t the economy—read now.

By MacKenzy Pierre

American Middle Class / Feb 16, 2026

The “Resilient Consumer” Is Real—But So Is the Interest Bill

Credit card balances are rising as savings fall. See what it means—and the 30/60/90 plan to escape 25% APR debt.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Feb 09, 2026

What To Do If You Get Fired With an Outstanding 401(k) Loan

Fired with a 401(k) loan? Avoid taxes, offsets, and deadline traps with this step-by-step checklist. Read now.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Feb 09, 2026

The Real Math of Money in Relationships

Split finances without resentment. Any couple, any income ratio. Use the worksheet + rules—start today.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Feb 03, 2026

Investing or Paying Off the House?

Invest or pay off your mortgage? See a $500k example with today’s rates, dividends, and peace-of-mind math—then choose your plan.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 30, 2026

Gold, Silver, or Bitcoin? Start With the Job—Not the Hype

Gold, silver or Bitcoin? Learn what each is for—and how to size it—before you buy. Read the framework.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 29, 2026

Florida Homeowners Pay the Most in HOA Fees

Florida HOA fees are surging. See what lawmakers changed, what’s next, and how to protect your budget—read before you buy.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 29, 2026

Why So Many Homebuyers Are Backing Out of Deals in 2026

Why buyers are backing out of home deals in 2026—and how to avoid costly surprises. Read the playbook before you buy.

By Article Posted by Staff Contributor

American Middle Class / Jan 28, 2026

How Money Habits Form—and Why “Self-Control” Is the Wrong Villain

Learn how money habits form—and how to rewire spending and saving using behavioral science. Read the framework and start today.

By FMC Editorial Team

Latest Reviews

American Middle Class / Feb 18, 2026

How Wealth Is Passed Across Generations in the United States: Mechanisms, Evidence, and the Policy Debate

How wealth passes between generations—trusts, taxes, and the debate. Get the facts, figures, and tradeoffs....

American Middle Class / Feb 16, 2026

The S&P 7,000: How Wall Street Disconnects from Main Street

S&P 7,000 can rise while wages, benefits, and towns fall behind. See why the market...

American Middle Class / Feb 16, 2026

The “Resilient Consumer” Is Real—But So Is the Interest Bill

Credit card balances are rising as savings fall. See what it means—and the 30/60/90 plan...