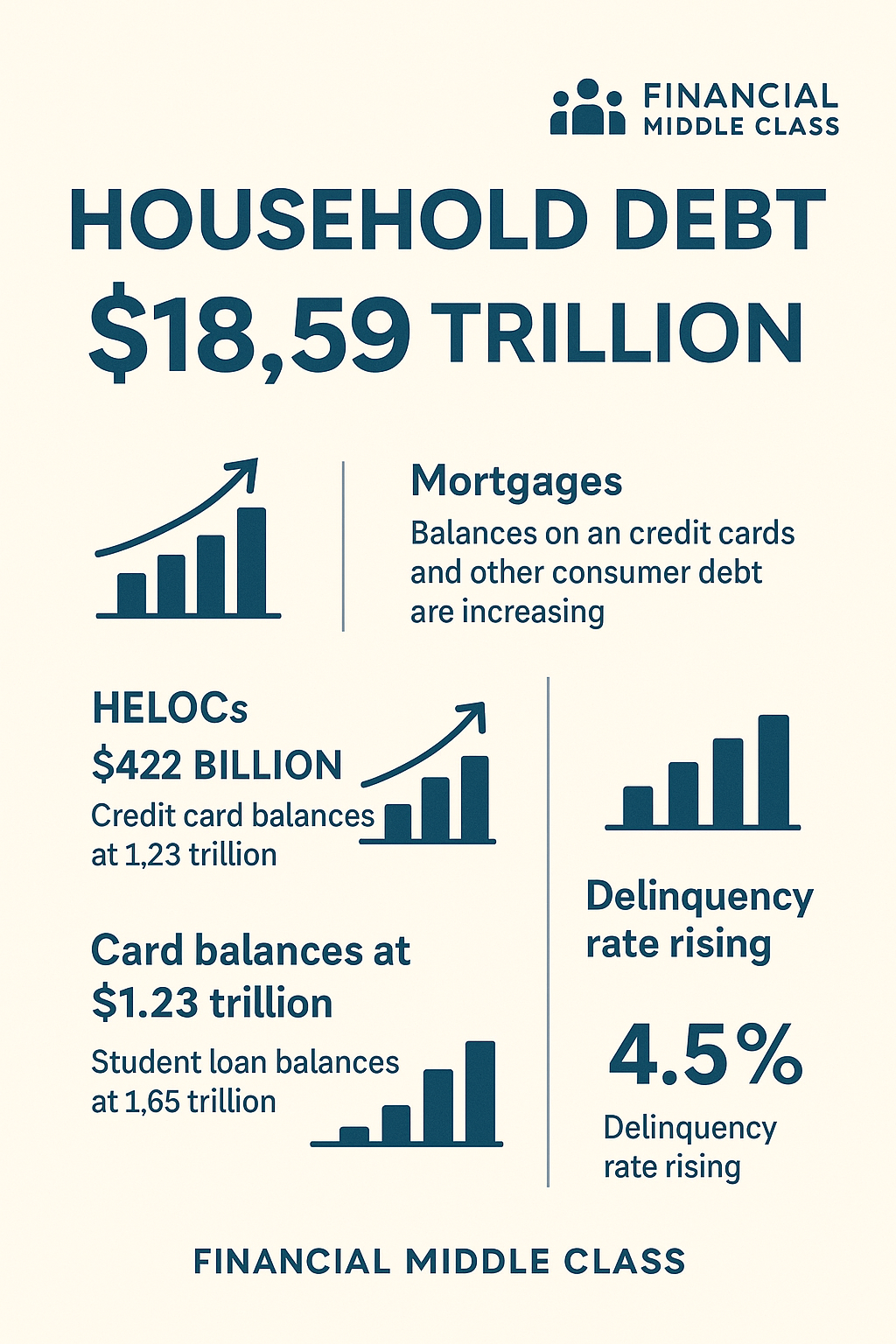

Household debt just hit $18.59 trillion.

That number is not abstract. It’s your mortgage, your car note, your credit cards, your student loans—and everyone else’s layered on top.

In the last quarter alone, American households added $197 billion in new debt. Total balances are now more than $4.4 trillion higher than they were before COVID.

If that continues, the middle class won’t collapse overnight. It’ll just keep drowning quietly.

The new Household Debt and Credit report from the New York Fed is telling a simple story if you know how to read it.

Mortgages went up. Home equity lines of credit went up. Credit cards went up. Student loans went up. Delinquencies are no longer falling—they’re inching back up from the floor.

If those trends continue, the fallout won’t look like 2008 with a sudden wave of foreclosures and headlines. It will look like more families stuck in place, more paychecks spoken for before they land, and more people using debt just to live a life that looks “normal.”

Most of that $18.6 trillion is tied to housing.

Mortgage balances climbed to $13.07 trillion, and banks wrote more than $500 billion in new home loans last quarter alone.

At the same time, home equity lines of credit—HELOCs—rose for the fourteenth straight quarter to $422 billion, now over $100 billion above their recent low.

Households are not just buying homes. They’re borrowing against them again.

If that pattern continues, housing will feel less like safety and more like a lever people keep pulling to stay afloat. A house that was supposed to be your anchor slowly becomes the thing you raid whenever the month doesn’t work.

Plastic is doing its own damage.

Credit card balances jumped to $1.23 trillion, nearly six percent higher than a year ago. “Other” consumer debts like store cards and finance loans are now around $550 billion.

Banks increased card limits by another $94 billion.

If that continues, more of your everyday life—groceries, gas, kids’ stuff, small emergencies—will be financed at 20% interest. A quiet, permanent surcharge on being middle class.

Delinquency is still “low” on paper, but the trend has turned. About 4.5% of all household debt is now in some stage of delinquency, and the Fed notes that more borrowers are starting to fall 90 days behind, especially on student loans.

If that continues, more families will cross an invisible line—from “stressed but current” to “behind and catching up for years.”

Auto and student loans are squeezing the working years.

Auto balances sit at about $1.66 trillion, and while the total hasn’t exploded, lenders are getting stricter with lower-credit borrowers.

If that continues, people with imperfect credit will still need cars, but the cost of getting to work will eat more of each paycheck.

Student debt stands at $1.65 trillion, with 9.4% of it now 90 or more days delinquent after missed payments returned to credit reports.

If that continues, a whole cohort in their 20s and 30s will spend the very years they’re supposed to be building wealth just repairing credit and trying to get back to zero.

The report also shows who is carrying the weight.

Middle-aged borrowers—roughly late 30s to late 50s—hold most of the country’s total debt, mostly mortgages and home equity. Younger borrowers hold less in dollars but more in unforgiving debt: student loans, cars, and cards.

They are also more likely to become seriously delinquent.

If that continues, the group that’s supposed to be forming households, having kids, and buying starter homes will keep showing up late in the data and paying higher prices for every mistake.

Geography makes the picture worse. High-cost states like California, New Jersey, and New York carry the heaviest debt per person. Delinquency and foreclosure rates are higher in boom-and-bust markets like Nevada, Florida, and Arizona.

If that continues, your zip code will matter as much as your work ethic in determining how fast you can climb out.

So what does all of this mean for you if you’re in the Financial Middle Class?

It means this report is not just about “the economy.” It’s about the direction your own balance sheet is drifting.

If total debt keeps rising, if more of that debt is tied to high-interest cards and “just put it on the line of credit” decisions, if more people quietly slip 90 days behind, then the middle class will not fall off a cliff—it will wear itself down.

Your job is not to fix the whole system. Your job is to decide whether you’re going to move with those trends or push against them.

Are you adding to the balances the Fed just counted, or shrinking them?

Are you using your house as a safety net or an ATM?

Are your cards a tool you pay in full each month, or a second paycheck with a 20% fee?

Are your next 12–24 months built around buying more lifestyle or buying back more control?

The report doesn’t answer those questions. It only makes one thing clear:

If the current patterns continue, the math will not magically break in favor of the middle class. So the middle class has to start breaking the patterns itself.