Before you come for my neck and start with the “what happened to you, weren’t you progressive?” yada yada—let me explain what I mean.

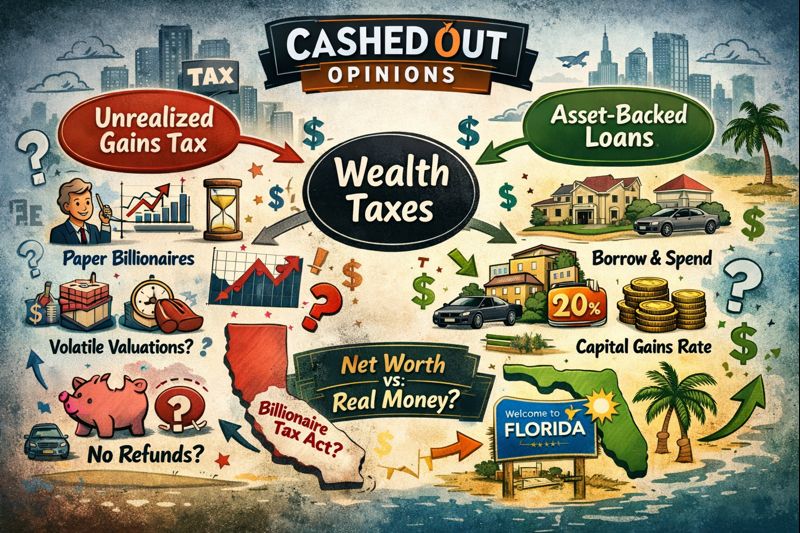

California has a proposed “Billionaire Tax Act” floating around that would hit residents with a one-time 5% tax on their net worth if they’re worth $1 billion or more. I think that ballot initiative is asinine. It’s right up there with the idea of a federal “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax” that the Biden-Harris administration backed.

And I’m telling you: as policy, that’s sloppy. Not because I’m a billionaire lover. Because the target is wrong. A net worth tax is basically a tax on unrealized gains.

Net worth is not a pile of cash sitting in a vault; it’s a valuation. It’s an estimate of what your assets might be worth if you sold them—minus what you owe. And that’s the first problem: California wants to tax something that might not ever turn into spendable money.

Say you’re an entrepreneur. You mortgaged the house. You drained the 401(k).

Then lightning hits. The company takes off. Somebody calls you a unicorn. And suddenly, on paper, you’re a billionaire.

But what are you really holding?

You’re holding a business that could still collapse. A valuation that can get cut in half overnight. Assets that might be illiquid as a brick. And a personal story where the risk was real, not theoretical.

Now here’s the key question—the one California has to answer without dodging:

If the state taxes you as a billionaire today… and tomorrow your valuation evaporates… do you get your money back?

Let’s use Elon Musk (not a fan, but this is the best example I can think of). He’s worth north of $600 billion, and part of that is his stake in SpaceX. There’s a strong possibility that SpaceX’s paper valuation never turns into realized gains—private valuations can drop, markets can change, and the company’s economics are still deeply tied to big contracts and long timelines.

The state would be better off imposing excise taxes on loans and lines of credit backed by capital assets. It can be 20%—the top federal long-term capital gains rate—or higher for habitual offenders.

Loans and Lines of Credit Backed by Capital Assets

Securities-based lending is a tax-deferral strategy that the ultra-wealthy use, and it’s quite simple. Instead of selling appreciating assets, they borrow against them for cash. Then they die and pass the assets on, where the tax basis is generally adjusted to fair market value at death—meaning a lot of the accumulated gain can disappear for tax purposes under current federal rules. Loan proceeds generally aren’t taxable income because you have to pay them back.

Here’s a clear example of how securities-based lending works. Let’s say Jensen Huang, Nvidia CEO, with a net worth of about $163 billion wants to buy a mansion for $50 million. Instead of selling Nvidia stock that has appreciated more than 1,000% since early 2023, he uses his Nvidia stock as collateral to get a $50 million loan from Morgan Stanley, paying the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) plus a spread—maybe just SOFR for someone as wealthy as him and a bank trying to win or keep the business.

Mr. Huang can rinse and repeat this process as long as the collateral holds, so he never has to realize his Nvidia gains and pay the government its share.

So Mr. Huang can borrow $50 million against a portfolio, buy the mansion, fund the lifestyle, move money around—without triggering capital gains tax, because he didn’t sell anything.

The government doesn’t get paid. Not because it’s illegal. Because the rules say the taxable moment is the sale, not the borrowing. And California can change that—and it will be a lot easier to get regular folks’ support because they don’t have the privilege to play financial jiu-jitsu with the tax code. When they earn wages, the government gets paid immediately—before their money even hits their account.

The entrepreneur who risked everything to build something is “a billionaire on paper.” But the person doing securities-based borrowing is turning paper wealth into real spending power—without selling, without realizing gains, without paying the tax you and I can’t dodge.

If California can’t tell the difference between a paper billionaire and a legacy billionaire who continues to borrow against appreciated assets to fund consumption, it’s going to learn the hard way—watching its tax base seek exile in my home state of Florida.